A Voyage ‘Round the World and Back in Time

Andy Colpitts

A Voyage ‘Round the World and Back in Time

Andy Colpitts

A Voyage ‘Round the World and Back in Time

Andy Colpitts

A Voyage ‘Round the World and Back in Time

Andy Colpitts

From Fathoms to Footlights: Whaling and Theatrical Lighting at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century

Andy Colpitts

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Deliciousness Deferred: The Introduction of Tomatoes to Europe

Giancarlo Valdetaro

Today, tomatoes are used the world over: in India, tomatoes are often used as the base for curries; in China, they can be stir-fried with eggs; in Nigeria, they form the basis for beef stew; in Spain, tomatoes are an essential component of gazpacho, a cold soup that also includes cucumbers, peppers, and herbs; in Brazil, they are the star in vinagrete, a form of slaw; and in Italy, of course, they are the basis for sauces combined with a variety of carbs and commercialized around the world. However, despite its presence in these dishes and its status as a staple in even more cuisines, tomatoes’ ubiquity is a recent historical phenomenon. Until the early sixteenth century, when Spanish conquistadors accelerated the pace of the Colombian Exchange through their victory over the Aztec and Inca Empires, tomatoes were a marginal, often-wild, only recently domesticated plant found in parts of South and Central America. Even after being introduced to a wider population through trade networks that spanned the globe, tomatoes were not central to many diets for hundreds of years, especially in Europe. Although there are similarities between these initial experiences with tomatoes in the Americas and Europe, they are revelatory of two distinctly different phenomena: the slow pace but incredible variety of ecological change in an otherwise-contained environment and the obstinance of white European prejudice against residents of the Global South.

South and Central American initial experiences with tomatoes are similar to their European successors in that tomatoes were not grown or consumed extensively at first. In the Andean region of South America and central Mexico, tomatoes grew as a wild fruit for centuries before Aztecs began to domesticate them shortly before first interaction with the Spanish (Smith, 15). Prior to this controlled cultivation, tomatoes exhibited a wide range of diversity due to the various geographies of the mountainous regions, whose multiple habitats and climates allowed for different varieties of tomatoes to thrive (Bergougnoux). Despite this long history, when Spaniards recorded the first accounts of tomatoes in Mexico, it was noted that the tomatillo –which had been domesticated in the area much earlier– was more important

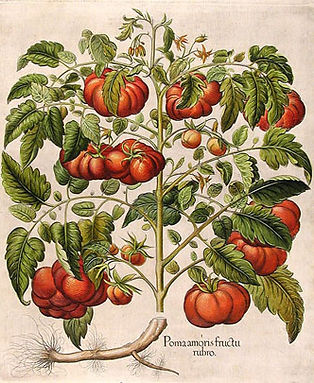

A tomato vine. In the centuries leading up to contact with Europeans, tomatoes steadily moved northward from South America into Mesoamerica.

to the local food environment. During this early period, this variety was used in sauces and salsas (Hyman). Meanwhile, although tomatoes were more resistant to rot and more colorful, they were still comparatively marginal in importance (Hyman). The trajectory of tomatoes in Europe followed a similar trajectory. Although they were quickly included in documents and publications on plants and wildlife, they were most often described as either dangerous or used for ornamental purposes as opposed to consumption, although there were regional variations (McCue).

Such regional variety is an additional commonality between the experiences with tomatoes in both the Americas and Europe. In South and Central America, the vast variety of tomatoes resulted from the diverse soils and climates of the Andean region along South Americas Pacific Coast and areas in Central America. Although areas in Mexico had the aforementioned tomatillo –called tomatl by the Aztec– the fruit that would become known as the tomato was originally indigenous to the Andes, inhibiting its adaption in areas farther North (Smith). In Europe, regional variation took the form of disparate adoption of tomatoes in cooking. In Italy, references to consumption of tomatoes were made as early as the 1580s (McCue). In Sevilla, they were being consumed by the year 1608 (Smith). Half a century later, at the House of Aguilar in Montilla –north of Málaga, near Córdoba– tomatoes were frequently listed on the menu and shopping list (Hyman). In Naples, the earliest known recipes were found in the late-seventeenth century and were said to have been sourced

When first introduced to Europe, tomatoes had a golden color. The Italian word, pomodoro, is actually derived from the initial moniker for a tomato, golden apple.

from Spain (Smith). This disparity between initial consumption and placement in cookbooks can have multiple, overlapping explanations. First, vegetables were not a significant part of the diets of the wealthy, for whom cookbooks were the primary audience. Indeed, in Iberia and Italy poor residents were the first adopters of tomato into their cooking (Hyman). Second, including a recipe in a cookbook required years of practice and experimentation, meaning it would have taken time for recipes with tomatoes to go through the necessary trial, error, and approval to get placed into cookbooks (Hyman). No matter the cause for this disparity within Southern Europe, though, it is nowhere near the duration of the wait between arrival and consumption of tomatoes in Central and Northern Europe. In Vienna, Northern France, and England, it took until the second half –and often the last twenty years– of the eighteenth century for tomatoes to be acknowledged as safe to eat. Even after their safety was accepted, Central and Northern Europeans found them much less enjoyable than their counterparts in Italy, Iberia, and even Southern France and Southern Germany (McCue).

The reason for this exacerbated disparity in diffusion gets at the main difference between regional variation in the Americas and Europe in adoption of tomatoes. In the Americas, it was ecological forces keeping Aztecs from domesticating tomatoes. Wind, birds, or migrating human populations were the ones moving the larger version of the fruit from the Andean highlands up to what is now Mexico (Hyman). In contrast, tomatoes didn’t spread as a food item in Europe due to misinformation based in humorism and its accompanying prejudice. Whilst declining to eat tomatoes and stringently advocating against them in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries especially, Europeans –with increased intensity in northern Europe– claimed in a number of ways that tomatoes were poisonous, rotten, and smelly (McCue). Although some of this is based on early mistakes classifying the plant as related to mandrake and nightshade, explanations that people who did eat it were doing so in spite of inferior nourishment or because it was a cold food for people living in hot weather demonstrate that these sentiments truly lied in a humorist outlook that rejected foods from the Americas (McCue).

Unfortunately for Europeans, this was not the only time they delayed enjoying a food that would become a staple of their diets. The hesitancy to adopt tomatoes, as well as the suspicion of soldiers serving in the Americas who developed a taste for the vegetable, are similar to the initial distaste for chocolate and tobacco Europeans expressed, especially when considering the cultural valuations included (Hyman). Together, the treatment of these crops by Europeans demonstrates how the racially hierarchical worldview they held not only harmed their victims in brutal, large-scale ways, but also deprived Europeans from enjoying the day-to-day pleasures the Americas offered.

Canning allowed for the conservation of tomatoes.

Bibliography

-

Bergougnoux, Véronique. “The History of Tomato: From Domestication to Biopharming.” Biotechnology Advances, Plant Biotechnology 2013: “Green for Good II”, 32, 1 (2014): 170–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.11.003.

-

Hyman, Clarissa. Tomato: A Global History. London, UK: Reaktion Books, 2019.

-

McCue, George Allen. “The History of the Use of the Tomato: An Annotated Bibliography.” Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 39, 4(1952): 289–348. https://doi.org/10.2307/2399094.

-

Smith, Andrew F. The Tomato in America: Early History, Culture, and Cookery. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1994.